By Om Malik

It’s Saturday in South Park. Kids are squealing. A man shadowboxes behind me. Sitting across from me on a not-so-clean bench are Bethany Bongiorno and Imran Chaudhri, partners in both life and work. They are co-founders of Humane, the San Francisco company behind AI Pin, arguably the first AI personal computer. (Also: What is an AI Pin?) We were meeting to discuss the next step in the company’s evolution. And what better place than the fabled South Park—erstwhile home to Twitter and Instagram, before they moved to a bigger future?

They launched about six months ago. Their promised device, the AI Pin, was supposed to free us from the tyranny of the phone and its screen. The square screenless device is a tad bigger than a smartwatch. It magnetically clips to your clothes. It looks like something right out of a “Star Trek” future. Press the device and ask it to make appointments or call an Uber.

What came into the hands of reviewers and eventually customers was nowhere close to the nirvana many had imagined. The gulf between the promise and reality had reviewers frothing at the mouth. One very influential reviewer called it the “worst product he had reviewed.” Others were equally or even more brutal.“The problem with so many voice assistants is that they can’t do much — and the AI Pin can do even less,” The Verge reported. The device had poor battery life, and heating issues, the laser display was subpar, and more importantly, the device felt quite laggy. The biggest cardinal sin, though, was that it didn’t really have a killer app in the traditional sense. For me, “AI” was that killer app.

It all generated so much attention in the first place because of the founders’ pedigree. Bongiorno had been at Apple for a decade as a top product manager for the iPhone and Mac operating systems. Chaudhri had been a designer there since 1995 and had become one of Steve Jobs’ trusted deputies, helping to design every top Apple product of the past two decades. The pair leveraged that pedigree hard, raising nearly a quarter of a billion dollars in VC funds from investors such as Marc Benioff, Sam Altman, SoftBank, and Tiger Global.

My initial experience with the device was a few months before the April 2024 launch. While AI Pin was still in development, I could see the promise. I was impressed by what I saw days before launch, though I didn’t get to experience it firsthand. And when I did, what bugged me were the problems caused by network latency. I bristled at the idea of paying $25 to T-Mobile for a poor 5G connection, on top of my monthly phone tariff.

Given that this was a highly personal computer, it would take a lot of data and information for it to become “personal” to me. That means spending time using the device. And the hallmark of AI devices is that they improve with time and software. It is not just AI devices—Apple’s watch of today is remarkably different from what was launched almost a decade ago.

Or maybe, I am prone to viewing the future with rose-tinted glasses. I know every new device that tries to pre-empt a generational shift in computing has problems. Whether it was the BlackBerry pager, Palm, Treo, or even the first iPhone—for me, new devices come with acceptable teething problems.

AI Pin was released in the social media era, with a slew of problems. Social media crucified the product, the company, and the founders. Everything from the company’s slick marketing videos to the founders’ attire or their attitude was fair game. They had more social media missiles lobbed at them than objects thrown at a Yankees fan in the Fenway Park bleachers. After the social media frenzy ended, other troubles compounded: product bugs and executive departures. The torrent of bad news didn’t end. Soon there were rumors of a sale.

Earlier this summer, The New York Times wrote a proverbial autopsy of the company. Buried in the Times’ report was a tidbit: HP was interested in licensing the company’s operating system.

DON’T CALL IT A PIVOT

Lost in the barbs about the botched hardware was the fact that a new kind of operating system powered the AI Pin. It was clear that AI Pin wasn’t merely a hardware wrapper for ChatGPT; it was software developed for the oncoming AI future.

Sitting across from me, Chaudhri is sharing details about lessons learned and his company’s core product, CosmOS, the AI operating system. The company now plans to license the software to those interested in AI-powered devices.

A day earlier, I saw demos of CosmOS performing AI Pin-like functions while operating inside a car’s dashboard. You could interact with the car’s dashboard by talking to it—call up your calendar, get directions, and update your next appointment for any delays. It made a smart speaker much more intelligent than, say, an Alexa device.

Chaudhri and Bongiorno are careful not to use the phrase pivot. “CosmOS was built to be universal from day one, so this isn’t a new direction,” Chaudhri said. Since they are not stopping selling the AI Pin and are now licensing the OS, they don’t think it is a pivot.

Not that a pivot is a bad thing. Pivots are par for the course in Silicon Valley -- just ask Slack co-founder Stewart Butterfield. In retrospect, this is the right path for the company to take. Why? Because even if AI Pin were a smash hit, they couldn’t sell enough AI Pins to become a large company. They would need a humongous amount of funding. There is a reason why building a hardware company is hard. Ask any founder who has tried it.

Licensing an operating system can be a lucrative business. Microsoft’s Windows windfall is legendary. However, there are other less obvious examples. In 1998, I wrote about a company called Integrated Systems that made an OS for devices ranging from dishwashers to microwaves. In 2000, it merged with Wind River Systems, and their OS powered all these devices that are computers but don’t look like computers — washing machines, for example. Wind River is now owned by Intel.

A series of operating systems have run point-of-sale systems and ATM machines. The Internet of Things created a market for embedded operating systems — mostly variants of Linux and Android. It makes perfect sense that with the proliferation of devices with AI inside, there will be an OS made for these AI-driven machines.

Alexa speakers gave us a hint of the future. AI Pin, Rabbit, Snap, and Meta’s glasses are evolutionary steps in this journey. As I have said earlier, “There is no doubt in my mind that AI devices are good signposts to a future that goes beyond phones and screens into a realm of invisible information interfaces.”

The idea of us talking to our machines, and our machines becoming more personal and offering personalized information and help, is now a question of how and when, not if or why.

WHAT IS AN AIOS?

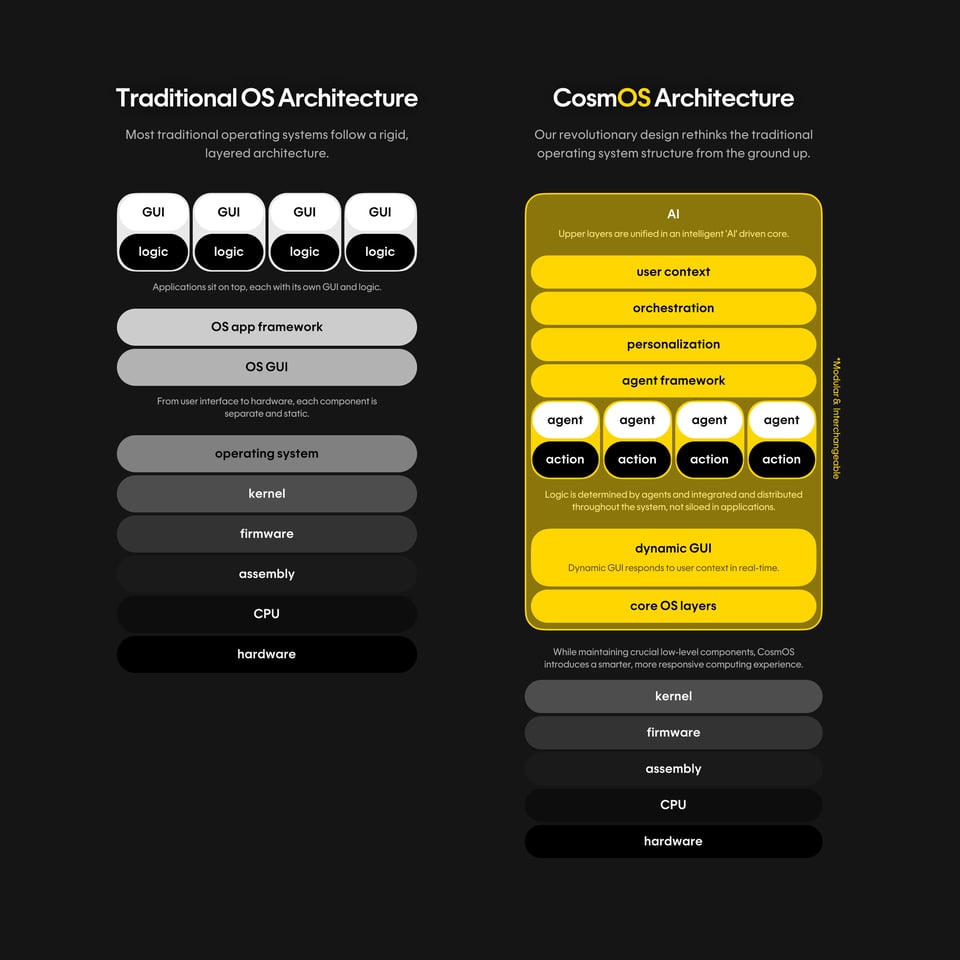

Traditional operating systems such as Microsoft Windows or Apple’s iOS rely on a predictable, almost rigid structure. There is a foundational layer that includes elements like firmware and kernel that interact with hardware and chips. On top of that, we have the operating system, GUI, and a framework for apps. Each app has its own interface and logic. There are clear boundaries.

As owners of computers and phones, we manually navigate menus and commands of apps. Each application requires different actions to work for us, making the experience feel siloed and disjointed.

An AI-focused operating system is agent-driven instead of application-driven. The agents - tiny bits of software - replace traditional apps. That’s faster and more intuitive. You don’t say, “I need to start the calendar app so that I can make a date,” you just tell the machine to make a date and the agent does it.

Let’s say you ask AI Pin to send a message to your mother. Unlike in the past, you no longer need to launch your messaging app, select a recipient, type a message, and hit send. Instead, you simply voice your request. The AiOS then works with various “agents,” understands your intent, accesses your contact list, crafts the message, and sends it.

Another example is a calendar app. It’s what we use to manage events or send reminders. If it needs location data or travel estimates, it must look for that information in another app or have that functionality built in. In an AI-first world, agents related to time, location, and traffic would work together and complete the same task faster.

"The traditional concept of an operating system was to allow you to operate hardware manually," said Chaudhri. "With advancements in AI, we can now remove that demand and let the computer handle the logic operations."

Every big technology company, notably Microsoft and Apple, is scrambling to reengineer its existing systems to work this way. CosmOS's advantage—at least theoretically—is that it's been architected from the ground up with the new AI era in mind.

LOOKING AHEAD

During our conversation, I saw the toll the past few months have taken on the founder couple. I am curious to know how they have coped with the reaction to the AI Pin. I have been in their shoes in a much smaller way. I have been a founder who failed with a startup. I have been an investor who has taken his lumps. I’ve seen my ideas or reasoning become conventional wisdom, just not when I thought it would become commonplace.

Just as no amount of money can turn a startup or idea into success (Color), no amount of bumbling can destroy a product (Twitter) whose time has come. As someone who saw the very first version of the AIPin, long before it became an AI Pin, I knew conceptually that Chaudhri and Bongiorno were onto something - that the age of AI computers was upon us. Just as grafting keyboards or touch screens onto old-school phones wasn’t the smartphone future we deserved, the idea of grafting AI onto current devices doesn’t make much sense long term. AI Pin was a good attempt at shifting gears and taking us in a new direction. I said as much in my piece about the need for experimentation with AI devices.

Licensing their operating system marks a shift from their earlier hardware-only strategy. In response to my question about licensing partners, Bongiorno said, “We have conversations in flight, but we’re not at the point of announcing anything formally.”

“When you’re doing something new and radical, you’re bound to face criticism,” Bongiorno reflected. “It was incredibly difficult. We had a choice — fold and hide or stand up, accept the feedback, and push forward. We believed in the vision, so we kept moving forward.”

“We had to stand up and accept the critique and feedback in front of our team, in front of the public, and just continue to push forward every single day,” Bongiorno said. “And it was really hard. Hard and painful. You’re right, it is really hard to get a second chance.”

“We have to do that by listening and iterating as quickly as we can,” she added. “And just continuing to move forward, making sure that people see what we’re doing. We’re not really sure how many more people want to hear from us directly right now. It’s more about seeing it in the work and seeing it in the product.”

I asked them if they had a chance for a do-over, would they do things differently?

“Obviously, there are a thousand things we would do differently,” Bongiorno said. “I think that, of course, is always the case.” Communicating about the product, its capabilities, and its realities is what the founders say they could have done differently. “There were some missteps in how we came off in certain things that are not very true to who we really are.”

I wondered if their launch and how they spoke about their product and its capabilities were influenced by their time at Apple — possibilities of technology and minimalistic imagery in slick launch videos are hallmarks of the iPhone maker.

“One of the interesting things about doing something new is that there’s really no right way to talk about it,” Chaudhri said. “We didn’t have the luxury of large marketing support to try different ways to talk about it or the luxury of time to talk about it.”

The crisis compelled the founders to seek external assistance, which they found in John Chambers, former CEO of Cisco Systems and a business legend. He invested both money and time to help the first-time founders manage the company. This support helped the company find focus, and the crisis compressed their timeline.

“We validated what we started to build over five years ago in that it arrived when we said it would,” Bongiorno said. “From that standpoint, I wouldn’t change a thing. I would probably just change how we talk about what we built.”

Licensing their operating system marks a shift from their earlier hardware-only strategy. But that’s not the way they see it. “It was always part of the plan,” Bongiorno said. “The AI Pin was an entry point because we needed the Pin to understand what a multimodal contextual computer would need in an OS.”

When we’re done talking, I feel optimistic about their chances. Given their Apple pedigree, it is not difficult to understand a focus on a singular device. But building a business around the concept of licensing operating systems requires a different kind of corporate muscle than a company exclusively making hardware. Sure, CosmOS is device agnostic and can be used with different processors and embrace different AI models. But still, when you have a licensing-centric company, you have many masters.

I hope they will have better luck with it than they did with the court of public opinion. For me, like my Vision Pro, the AI Pin still finds use during my day. It has improved. We have learned a lot about each other. It has become another camera for me—capturing images when I don’t want to use my iPhone. I whisper it a few notes. AI Pin isn’t a smartphone replacement. I still love my phone—and can’t do without it. I am still hopeful that eventually, it will become a permanent fixture in my life.

Additional Reading:

I'm struggling to work out what's so special about their AI OS."Our revolutionary design rethinks the traditional operation system from the ground up" would be more convincing if the bottom of the CosmOS architecture diagram didn't resemble the traditional OS architecture exactly, which makes you wonder where they think the ground starts. And saying that in traditional OS architectures "each component is separate and static", but in CosmOS "logic is determined by agents and integrated and distributed throughout the system, not siloed in applications", sounds good, but could just mean that there's no security model and you have a bunch of tiny agents all effectively running as root.

“There is no doubt in my mind that AI devices are good signposts to a future that goes beyond phones and screens into a realm of invisible information interfaces.” The idea of us talking to our machines....is now a question of how and when, not if or why. Hmmmmm, so the ubiquity of face-on-screens fracking our social lives will be replaced by a pervasive murmuration of voices, the Hum of robotic conversations singing the cybercosm. A kind of social media tinnitus, I guess.

I don’t share your optimism. The major AI companies have APIs that anyone can build upon. They are providing 90% of the brains. The special sauce—sort of—may be in how you interact with the models. But at the end of the day, the wonderful aspect of a mobile phone is that it’s a truck and no on e wants to carry multiple dedicated devices.

So much of the issue with the launch of the AIPin was the overwhelming hype and arrogance from the founders and Head of Dev, they set themselves up for a big fall. I guess you do have to shout loud to be heard, but the pedigree of the founders probably meant they could have been more understated and it might have gone down better.

I agree with how they launched the company.

You have to remember that when you have spent that long at a company like Apple, the legacy of that experience can make you follow a playbook that doesn't work with startups. In hindsight, they know better, but we wouldn't have this discussion if the product worked as promised. I feel that was the crux of the real issue.